Eton and Brought Up (Sunday Times, June 3, 1962)

By Ian Fleming

The Fourth of June. By David Benedictus. (Blond. 18s.)

I don’t think the old music-hall gag is inappropriate. In this brilliant first novel Mr Benedictus has swallowed his public school life and regurgitated it because some of its bones stuck in his throat.

It was inevitable that before long we should have an angry young Old Etonian, and Etonians, wincing as they will beneath the author’s lash, will at least admit that the cane is being wielded by a supremely talented hand.

Perhaps The Fourth of June should have been reviewed by one of the author’s own generation. The last book on Eton I read, apart from the scintillating fragments by Connolly and Orwell, was One of Us, a romantic novel in verse by Gilbert Frankau, some thirty years ago. To older generations of Etonians, Mr Benedictus’s bubbling, steaming brew of adolescent life, peppered with the á la mode four-letter words, will be almost unrecognisable. But only almost, because beneath the author’s vicious brush-strokes the ancient brickwork, the remembered totems and taboos come through, often with exquisite brilliance.

Briefly, the story is of Scarfe, a grammar-school boy bent and finally broken by the snobbery, sadism and sexuality (hetero-, homo-, and auto-) which, in the Benedictan view, are the devils in the machine of an Eton education, and this theme, for a man with as sharp a pen as the author’s, is, of course, a natural.

Knowing nothing of the strains and stresses suffered by the modern Scarfes beneath the weight of Eton and its customs, it is difficult for an older Etonian not to argue that in his day the psychologically halt and lame boys also went to the wall, and he might complain, I think legitimately, that the author has outstripped the bounds of truth in laying Scarfe’s downfall to the three S’s mentioned above.

I cannot, for instance, swallow the Bishop with his militant religiosity combined with voyeurism. I do not believe in the sadism of Defries, Captain of the House, in the strangulation of the hero’s pet bird, nor in the pusillanimity and downright venality of the housemaster and the headmaster (in a foreword Mr Benedictus makes plain what is obviously true, that none of his characters have any relation to any living person) when faced with blackmail by a boy’s mother who finally pays off the housemaster with her body.

These, and many other incidents, however brilliantly described—an elder boy who hires out his younger brother is a sharp and disagreeable case in point—are sheer caricature, and to give poor Scarfe festering wounds which sent him to the sanatorium after being tanned by the Captain of the House as a punishment for a breach of the rules, which both culprits could have explained, is, to this former target of cane and birch, incredible.

And was it really necessary to be so much involved in the angry swim as to need to direct a harsh side-kick at Royalty?

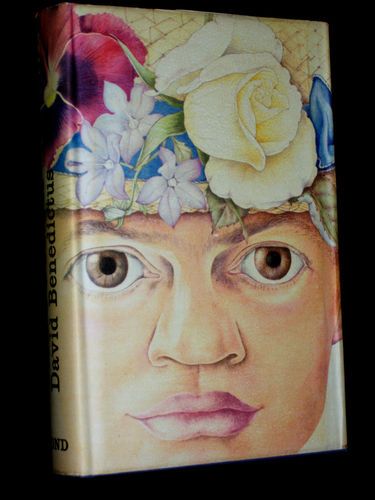

But these are criticisms of a reader who was fascinated by one of the most brilliant first novels since the war, written with rapier wit, acute observation and a perceptive eye for each of the lesser characters. The style is sharp and professional (though Mr Benedictus will kindly write out “éminences grises”—page 21—a hundred times) and the whole devastating package is embellished by the Jacket of the Year.

We shall hear more of Mr. Benedictus, so I informed myself about him. He is 23, the son of the managing director of a famous London store, and he was Captain of his House at Eton. Then came Balliol and the State University of Iowa to learn play-writing . He is now with the B.B.C.

Which of these institutions will bend next to the harsh block?

The reason Ian Fleming reviewed this novel apparently was its “Jacket of the Year” by none other than Richard Chopping, Fleming’s favorite Bond book cover artist:

For more information, consult the article “Blessed by Fleming, Adorned by Chopping – ‘The Fourth of June’”.

My crude guess is that Chopping asked Fleming to review The Fourth of June as a favor, and though Fleming hated the novel’s portrait of Eton and said so, he sweetened his review with some blurbable praise (“one of the most brilliant first novels since the war”).

Interested potential readers should be informed that the most recent reprint of the book dispenses with Chopping’s cover. Speaking only for myself, I’ve never been crazy about Chopping’s trompe-l’œil book covers, even for the Bond novels.