Note: This week brings another treat—the complete Desert Island Discs interview with Fleming. Only nine minutes of the audio survive, but thanks to the kindness of a fellow researcher and collector I can now share with you the transcript of the entire show. The interview was recorded in approximately 10 segments. Four were retakes, and though Fleming’s answers were usually identical I’ve included a few answers from the original takes. There are one or two bits where the transcriber was unable to catch what was said, and these are indicated with “[…]”

Desert Island Discs

Ian Fleming

Transcribed from a Telediphone Recording from Talks/General Division—Sound; 12th June, 1963

ROY PLOMLEY: How do you do ladies and gentlemen? Our castaway this week is a best-selling author. He is the author of the James Bond books, the ingenious thrillers about a British secret agent who’s licensed to kill. It’s Ian Fleming. Mr. Fleming, what effect do you think solitude would have on you?

IAN FLEMING: I think I would enjoy it very much. I’m rather solitary by nature, and I’ve always wanted to live on a desert island.

PLOMLEY: You’ve have no particular worry?

FLEMING: Not that I know of, unless I got an abscess in my tooth, or stumped my toe on a scorpion fish.

PLOMLEY: What would you be happiest to get away from?

FLEMING: Noise.

PLOMLEY: Mm. Does music play much [of a] part in your life?

FLEMING: No, very little indeed. I’m afraid this is a very light-hearted selection.

[Take 1: No, it doesn’t really. I only play gramophone records—sort of sentimental light ones for entertaining myself—in the evening with a drink or two.]

PLOMLEY: You’ve never studied music? You don’t play an instrument?

FLEMING: No, and I avoid concerts like the plague.

PLOMLEY: From what point of view did you pick your records? Are you looking back? Are you looking hopefully forward to the future? Is it mood music? What is it?

FLEMING: Well, I think it’s mostly mood music. It’s evocative of various times in my life and of er—girlfriends.

[Take 1: Well, I think it’s probably mood music. I think if one was on a desert island, you’d want to recall memories, possibly of girlfriends in one’s past and I’m afraid there’s certainly nothing very serious in my selection.]

PLOMLEY: What’s the first one?

FLEMING: The first is by Jack Smith, the famous Whispering Baritone, and this is a sentimental memory of my public school, Eton. He was a tremendous favourite with all of us there.

PLOMLEY: And what’s he singing?

FLEMING: He’s singing “Cecilia.”

Record 1

PLOMLEY: “Does Your Mother Know You’re Out Cecilia?.” Whispering Jack Smith. What’s your second choice?

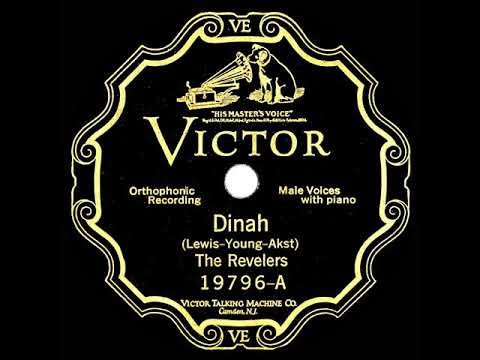

FLEMING: The second choice is The Revellers, another old, very old favourite of my generation, singing “Dinah.” They were a wonderful quartet and this recalls my period at Sandhurst.

Record 2

PLOMLEY: The Revellers singing “Dinah.” Mr. Fleming, where were you born?

FLEMING: I was born in London.

PLOMLEY: You told us you went to Eton. I believe your main distinction there was in athletics.

FLEMING: Yes, it was. I’m afraid I wasn’t terribly good at my books.

PLOMLEY: Victor Ludorum twice and public school hurdles. And then Sandhurst?

FLEMING: Yes, I went to Sandhurst, with the idea of going into the Army, and into the Black Watch incidentally, but then it was decided to mechanise the Army and me and a lot of my friends decided we didn’t want to be—what we thought then would be—large scale garage mechanics.

PLOMLEY: So—

FLEMING: So I had a go at the Diplomatic and learnt my languages for it, and I passed in seventh, but there were only five vacancies, so I decided not to have another go, but to go straight in and start earning some money. So I joined Reuters, which was the nearest thing to the diplomatic in a way, because I could use my languages, German and French and Russian, and I had a wonderful time at Reuters. I was a correspondent in Moscow and Berlin and all over the place, and of course I learnt there the sort of good straightforward—or at any rate straightforward—writing style everyone wants to have if they’re going to write books.

PLOMLEY: How long did you stay with them?

FLEMING: I stayed with them for three years, but then I wanted to earn some more money, and Reuters wasn’t very keen on paying large sums in those days—I’ve no doubt they’re much better now—and so I went into the City, but I didn’t get on very well there, because I’m not very good at making money as such.

PLOMLEY: How do you mean?

FLEMING: Well, I mean just pure making money. I must do something that entertains me; if it makes money at the same time, well that’s all the better for me.

PLOMLEY: Yes. Well, then the war came along, and you joined the Navy and became personal assistant to the Director of Naval Intelligence. Well, this led, not surprisingly, to some rather violent action I believe.

FLEMING: Well, not so much that, really. It was a very interesting life. I took part in the Dieppe raid, which was a very bloody affair, and I had some exciting adventures round the world, and all together I couldn’t have had a more interesting war, if one can have a interesting war.

[Take 1: Well, a certain amount you know, but then I was deskbound in the Admiralty for a great deal of it, but I went on the Dieppe raid and one or two forays around the world, and I really had a wonderful war, as far as one can have an wonderful war.]

PLOMLEY: And presumably your Naval Intelligence experience provided some useful source material for your later books.

FLEMING: Yes, it taught one what one could say in writing thrillers and what one couldn’t say. And of course it taught you really how the intelligence machine does work. I can’t say that of course I tell that exactly in my books, because they’re fiction and the whole thing is much larger than life, but as I said, at least it tells you what mistakes not to make.

PLOMLEY: And when the war ended?

FLEMING: Then I went to the Sunday Times, to the Kemsley newspapers and I became their foreign manager. They didn’t have a foreign department in those days, and it was my job to place correspondents all round the world and look after their welfare and see that they write plenty of intelligent stuff.

PLOMLEY: Yes. And you had that post until quite recently?

FLEMING: Yes, until Roy Thompson took over the group, and now I’m still mixed up with them vaguely as a so-called editorial advisor.

PLOMLEY: Well, let’s have your third record. What next?

FLEMING: My third record is Edith Piaff, the famous Parisian chanteuse, singing “La Vie En Rose,” which again has sentimental associations for me.

Record 3

PLOMLEY: Edith Piaff singing “La Vie En Rose.” Now your book. You’ve written now what—11 James Bond books?

FLEMING: Well, there’s actually twelve, because the next one has just gone to my publishers.

PLOMLEY: Yes, that’s one a year.

FLEMING: That’s one a year.

PLOMLEY: So the first one then, what, 1950—

FLEMING: ’52, written in ’51 I suppose. Yes.

PLOMLEY: Had you had this character growing in mind for a long time?

FLEMING: No, I can’t say I had really. He sort of developed when I was just on the edge of getting married, and I was frenzied at the prospect of this great step in my life, after having been a bachelor for so long, and I really wanted to take my mind of the agony [Laughter] so I decided to sit down and write a book.

PLOMLEY: Yes. Is Bond based on any particular person or combination of persons?

FLEMING: No, not really. He’s sort of mixture, a fictional mixture of commandos and secret service agents that I met during the war, but of course entirely fictionalised.

PLOMLEY: Yes. Is there much of you in it?

FLEMING: I hope not. People do connect me with James Bond, simply because I happen to like scrambled eggs and short-sleeved shirts, and some of the things that James Bond does, but I certainly haven’t got his guts nor his very lively appetites.

PLOMLEY: Now the first James Bond book was an immediate success.

FLEMING: Yes it was.

PLOMLEY: How long do these books take you to write?

FLEMING: Six weeks to two months, the actual writing, but I never correct as I go along, I try and get pace into the narrative by sitting straight down at the typewriter, but then of course I do two or three months correction afterwards, and then one has to correct the proofs and so on, so it takes about a year all together, let’s say.

PLOMLEY: Are you a systematic worker? Can you work so many hours a day, regularly?

FLEMING: Yes, I find I have to. I work for about three hours in the morning and one hour in the evening, and I find that unless I stick to a routine, if I just wait for genius to arrive from the skies, it just doesn’t arrive; I just get on with the work.

PLOMLEY: You write these books always at your vacation home in Jamaica—

FLEMING: —Yes.

PLOMLEY: Do you look forward to writing a new one every year?

FLEMING: Well I don’t really unless I’ve got it firmly fixed in my mind. And of course this is a very bad period for me, this time of the year, because I’m trying to work out the next adventure of James Bond, which has got to be written in January or February, and of course I’m always rather in despair thinking I’m not going to have enough book to write.

PLOMLEY: Yes. There’s been a cumulative rise in sales since the first book.

FLEMING: I think there has, with the exception of the last one, let’s say last year’s one, which was The Spy Who Loved Me, when I tried to break away from my normal formula, but the readers were so furious that James Bond didn’t appear until about three quarters of the way through, and that it was written ostensibly by a girl—

PLOMLEY: In the first person.

FLEMING: —That I must confess it wasn’t a success, and it took quite a beating from the critics.

PLOMLEY: And now the books are being made into films.

FLEMING: Yes, they’ve made Dr. No already and it’s been a tremendous success in England, and even more of a success I think in America, where it’s opened several weeks ago, where it’s breaking records. They’re now doing From Russia With Love and I went out to see them in Istanbul with the unit at work and I was tremendously impressed with the casting and the way the script had been written, and I think it’s going to be an equal success.

PLOMLEY: They’re going to do the whole James Bond catalogue.

FLEMING: They’ve got an option on doing all the books, yes. One after another.

PLOMLEY: Well, let’s have Record 4. What are we going to have next?

FLEMING: That’s the Ink Spots’ “If I Didn’t Care,” which is the first record that made them famous in 1944, and I’m devoted to the Ink Spots, all their records, and I play them constantly, every week.

Record 4

PLOMLEY: The Ink Spots’ “If I Didn’t Care.” 11 best sellers in 11 years and very profitable film sales. Now on the face of it, that looks like unmixed success, but some of the press notices haven’t been all that glowing. They’ve accused you of being sadistic and [including] too much sex. Taking the charge of sadism first, your torture scenes are pretty beastly in some of the books.

FLEMING: Well, I don’t know how many you’ve read, but they’re nothing to…what they really are in real life, and I think the old days of the hero getting a crack over the head with the cricket stump have rather gone out and we’ve all been considerably wiser since the last war, and I’ve tried to bring verisimilitude into these books—and it’s certainly true that the critics have occasionally found them pretty strong meat.

PLOMLEY: What effect do you think these scenes have on the average reader? Are they going to give him unhealthy ideas? Is this vicarious violence a harmless way of sublimating aggressive tendencies?

FLEMING: Well, I think that’s a way of putting it. I was brought up on what they used to call fourpenny horrors and I can’t remember that any of the excitements of the sort of […] Chinamen, and horrible Germans and so on and so forth, ever did me any harm. All history is sex and violence, and I think it’s ridiculous to go on writing thrillers in the old Bulldog Drummond-John Buchan way, when life has come on so fast past this.

PLOMLEY: Yes. Well, sex—Bond is a non-stop womanizer and he takes his sex where he finds it, almost as casually as he takes a drink.

FLEMING: Well, he has one girl per book approximately and that’s one a year. He’s a bachelor and he moves around the world pretty rapidly, and I don’t see any great harm in that myself.

PLOMLEY: He’s unusually fortunate in meeting these lovely and cooperative girls.

FLEMING: Yes, I envy him.

PLOMLEY: The last Bond book has achieved a new importance. It’s been issued in a handsome limited edition at three guineas a copy. Is this a sign of Bond in High Society, in top people literature?

FLEMING: I don’t think so really. I think it was just the publisher’s idea and apparently they managed to sell all the copies so it can’t have gone far wrong.

PLOMLEY: I mentioned some British criticism in the British press of the books. There’s another quote from a Russian paper that I think is rather more serious, and it accuses the James Bond books of being violently anti-Russian and it does seem justified. Invariably your villains are a pretty deep-dyed bunch of Russian thugs, and at a time when Anglo-Soviet relations are rather important, is this a responsible attitude?

FLEMING: Well, it’s all very fine, but these are fiction and one’s got to have an enemy. In the old days there used to be the Chinese and the Germans and various other nationalities, and when you come to think of some of the cases of about Russian espionage, there was one quite recently in Stuttgart, where a man had been sent by the Russians and had successfully murdered three West Germans, with a cyanide gas pistol. Well, if they will go on playing that sort of trick they mustn’t expect to be completely white-washed.

PLOMLEY: Mm. Still, you will admit that Bond is something of a deep-dyed thug himself.

FLEMING: Oh yes, certainly. He has to be or he couldn’t defeat the other deep-dyed thugs. It’s a world of thuggery.

PLOMLEY: Let’s have record No. 5.

FLEMING: No. 5 is Rosemary Clooney—“This Old House.” It makes a very fine noise this record, and I’m devoted to it and I’m also devoted to Rosemary Clooney’s appearance on the sleeve; and I assume I should be allowed the sleeves as well as the records, so that she can act as a pin-up girl on the nearest palm-tree.

Record 5

PLOMLEY: Rosemary Clooney, “This Old House.” All your books Mr. Fleming show tremendous attention to detail. You’ve obviously done a great deal of background research. Have you ever slipped up at all in any of the James Bond books?

FLEMING: Yes, I’m afraid I do from time to time. I take a lot of trouble not to, but inevitably things slip past my publishers. [Take 1: Oh constantly. It’s actually terrifying the number of mistakes I make, because I try to be accurate]

For instance in the last book the girl goes into a bar in the Casino and orders half a bottle of Pol Roger champagne. Well, it just turns out that Pol Roger is the one champagne firm that doesn’t turn out half bottles.

PLOMLEY: Good Lord.

FLEMING: And again, some friend commented on the fact that when Bond drives up to his headquarters in Regent’s Park and smells the smell of burning leaves and realises that summer has come to an end, I was making a mistake because Regent’s Park is now a smokeless zone. Well, that’s very helpful but I find that other people make mistakes. Shakespeare for instance had clocks chiming in ancient Rome, and other people have made errors of one kind or another—

PLOMLEY: Yes, somebody always writes in and tells them.

FLEMING: Yes, it’s very helpful of them and I try to correct them in later editions.

PLOMLEY: How much longer do you think you can keep Bond going? Is he a job for life?

FLEMING: Well, I don’t know, it just depends on how much more I can go on following his adventures.

[Take 1: Well, it just depends on how long my puff lasts, so to speak. It’s a question of invention.]

PLOMLEY: You don’t feel that he’s keeping you from more serious writing?

FLEMING: No, I’m not in the Shakespeare stakes, I’ve got no ambitions.

PLOMLEY: You do an occasional major piece of reporting. You went round the world for the Sunday Times quite recently.

FLEMING: Yes, that was a series called Thrilling Cities, which is coming out as a book in October.

PLOMLEY: Have you anything more like that lined up?

FLEMING: If I found something very exciting I’d love to do it you know, but again it’s a question of how much you can crush into the week, and I’ve invented the Fleming two-day week and I’m trying to stick to it.

PLOMLEY: Right. Record 6 now.

FLEMING: Record 6 is “A Summer Place” by Billie Vaughan, and I just happen to like this, because I think it’s a wonderful piece of light orchestration.

Record 6

PLOMLEY: Billie Vaughan and his orchestra playing Max Steiner’s theme from “A Summer Place.” Mr. Fleming, would you be an efficient castaway on this island?

FLEMING: I think I might be. I love underwater swimming and if I could make a spear out of a piece of bamboo, and get some sort of covering for my eyes, I think I could keep myself alive. I’ve always like the idea of building a house of palm-thatch and so on and keeping the scorpions away with a big ditch round it.

PLOMLEY: Could you build a craft?

FLEMING: Well, one could always build some sort of craft. How seaworthy it’d be I’ve no idea.

PLOMLEY: Well, how’s your navigation? Would you try to get away?

FLEMING: Very bad indeed. I’d cast myself loose if I wanted to find a dentist somewhere, but that’s as far as I could go, I think.

PLOMLEY: Record No. 7 now.

FLEMING: That’s the old Anton Karas, at his zither, playing the Harry Lyme theme. I enjoy the record because it’s rather a thriller writer’s record and it’s evocative of Vienna, which I’ve always enjoyed.

Record 7

PLOMLEY: Anton Karas, the Harry Lyme theme. Now we come to your last one Mr. Fleming. What have you chosen for the end?

FLEMING: The last record is Joe Carr playing “Darktown Strutters’ Ball,” and this is just a splendid hell-raiser, when I want to wake the echoes and feel perhaps slightly lonely.

Record 8

PLOMLEY: Joe “Fingers” Carr, “Darktown Strutters’ Ball.” We’ve heard your eight records Mr. Fleming. If you could take only one of this eight, which would it be?

FLEMING: Well, that’s a very difficult question, but I think on the whole I choose the last one, Joe “Fingers” Carr, because he makes this tremendous racket that would keep the ghosts away, and it would cheer me up if I was—as I say—if I was feeling rather gloomy.

PLOMLEY: And you’re allowed to take one luxury with you. What are you choosing?

FLEMING: If I couldn’t take my wife, I’d have a typewriter with plenty of ribbons and paper.

PLOMLEY: For what? More James Bond books?

FLEMING: Well, that we’d have to see, what there was to write about on the island.

PLOMLEY: All right, and one book to take with you, apart from the Bible and Shakespeare.

FLEMING: Well, this is perhaps the only sort of serious note in this programme, because in fact I’d probably take War and Peace, which I’ve never read but in German, because I enjoy the German language and I could both practice my German and read War and Peace at the same time.

PLOMLEY: Right. And thank you Ian Fleming for letting us hear your choice of Desert Island Discs.

FLEMING: Well, it’s been great fun and I hope it wasn’t too lighthearted.

PLOMLEY: Goodbye everyone.